Processing the Oil

When the barrels of whale oil were unloaded from the ships, they were sent to refineries in New Bedford and other nearby coastal towns. Most oil had to be purified before it could be used in lamps or to lubricate machinery. While on board ship, blubber, dirt and sea water had gotten mixed into the oil.

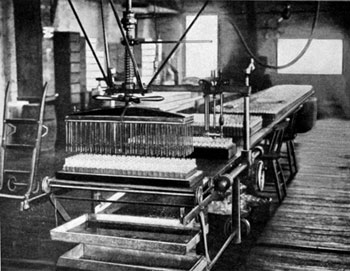

The oil processing industry took full advantage of New England’s seasonal temperature changes. At the refinery, the oil was first taken to a “bleach house” and heated in giant kettles to remove seawater, blubber and dirt that had become mixed with the oil. It was then sent to a shed to chill completely during the late fall and winter. The cool temperatures made the oil very thick. On a warmish winter day, the thickened oil was taken to the big “candle house” and shoveled into bags. A press squeezed liquid oil out of the bags and contained the thicker material for later processing. This first yield of oil was the most valuable because it stayed liquid at low temperatures and could be used during New England winters.

In the spring, the oily substance that had been returned to the shed to further chill was pressed again. This time, a much smaller amount of oil came out of the presses. This oil stayed liquid only to about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, so it was worth a bit less. What was left in the bags was heated again in giant kettles and poured into big molds where it cooled into blocks. In summer, when these oily bricks began to ooze from the heat, they were ground up and pressed again. This “summer oil” was the least valuable oil, because it stopped being liquid at about 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration